Disappearing Cheese Factories in America’s Dairyland

John A. Cross

University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh

The number of Wisconsin farms with milk cows fell by over 90,000 during the past fifty years (Cross 2001, WASS 2010). This drop, together with the rise in mega-dairy operations where many hundreds to thousands of cows are housed in free-stall barns, has resulted in tremendous changes to the state’s dairy farming landscape. Not only did Wisconsin lose eighty-seven percent of its dairy farms over the past half century, but the state lost most of its cheese factories. In 1920 Wisconsin had 2,771 cheese factories (Ebling et al. 1931). Their number peaked two years later, when 2,807 cheese factories were counted. By 1960 that number had fallen to 808, and now only 126 cheese factories are operating (WDATCP 2009). The state has also lost most of its creameries and condenseries, but this paper focuses upon the cheese factory because they were so much more prominent upon Wisconsin’s dairy landscape.

Three-quarters of a century ago the crossroads cheese factory dotted Wisconsin’s rural farming landscape. The presence of these cheese factories was particularly common within those parts of the state that were too distant from the Chicago and Milwaukee metropolitan areas to ship their milk for its consumption in fluid form. Furthermore, cheese factories shipped a far less perishable product, and thus could be profitably operated at localities not along railroads. At the time the Wisconsin Crop Reporting Service prepared its bulletin on Wisconsin Dairying and mapped dairy farms (Ebling et al. 1939), the preponderance of dairy farms in southeastern Wisconsin were producing milk for the urban market. Those dairy farms within southwestern, east central, and northeast Wisconsin, as well as those located in the southern part of the North Central Wisconsin agricultural reporting district, particularly the swath across Marathon and Clark counties, focused upon sending their milk to cheese factories. Those dairy farms within west central Wisconsin relied more heavily upon creameries as a destination where their milk was converted into butter.

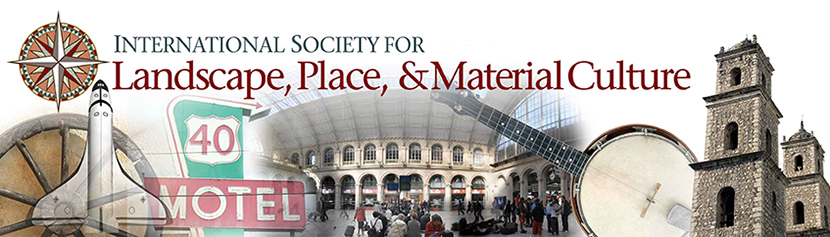

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of cheese factories in Wisconsin in 1938. Map prepared by Wisconsin Crop Reporting Service and reproduced from Ebling, et al. 1939.

Cheese factories were once densely distributed across several milk producing areas of Wisconsin, as shown in this map published by the Wisconsin Crop Reporting Service in 1938 (Figure 1), when Wisconsin had 1,917 factories operating. The early cheese factories, which required less milk to operate than either a creamery or condensory, were dependent upon a supply of fresh milk that was initially delivered by horse and buggy, “sharply restrict[ing] the radius of milk procurement…when efficient means of refrigeration were lacking"; (Lewthwaite 1964: 104). As Glenn Trewartha (1926:305) explained eighty-five years ago, “[t]he rugged and much dissected driftless territory of southwestern Dane, eastern Iowa and La Fayette (sic), and western Green counties, with its poorer rail and highway service, has remained the stronghold of the small cross-roads cheese factory.” Indeed, when Trewartha described Green County’s cheese industry, that county averaged one cheese factory for each four square miles of its land area.

At the time of their peak numbers, during the early to mid 1920s, ten counties each had over one hundred operating cheese factories (Ebling et al. 1931). Although Marathon County counted 157 cheese factories in 1922, not surprising given its status as the state’s largest county, smaller Dodge County had 170 cheese factories that year, down from its high of 178 in 1918. Green County had 213 cheese factories in 1910, and its number still exceeded 150 in the early 1920s (Ebling et al. 1931). Other counties that had at least one hundred cheese factories at their peak included Clark County in north central Wisconsin, Fond du Lac, Manitowoc, and Sheboygan Counties in east central Wisconsin, and Iowa and Lafayette Counties in southwest Wisconsin.

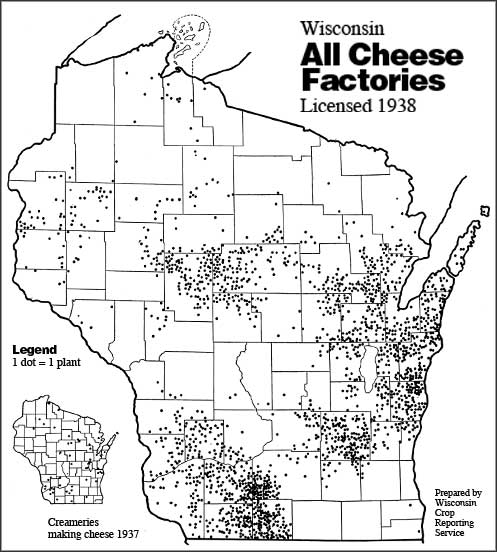

Figure 2. Spatial distribution of large and small cheese factories in Wisconsin in 2009. Map prepared by author.

Figure 3. Union Star Cheese Factory in Zittau, Town of Wolf River, Winnebago County. This cheese factory was built in 1904.

Today, not only does Wisconsin have far fewer cheese factories, but Wisconsin’s dominant role in the nation’s cheese production has fallen. While the state produced sixty-three percent of the nation’s cheese in 1929 (Ebling et al. 1931), that share has now fallen to just over twenty-five percent (NASS 2010). Although some relatively small family-operated cheese factories remain in business, most of Wisconsin’s cheese production now comes from industrial-sized operations (Figure 2). These larger factories are scattered across the same general areas where most of the smaller operations are found, although the smaller operations appear slightly more frequently in portions of southwestern and west central Wisconsin.

Figure 4. Salemville Cheese Factory in Town of Manchester, Green Lake County. This factory was purchased by the Amish to provide a market for their milk which is transported in ten gallon cans.

Only twenty-six percent of Wisconsin’s cheese factories in 2009 were categorized as manufacturing under one million pounds of dairy products per year. Examples of such smaller factories include the Union Star Cheese factory (Figure 3) in the Winnebago County hamlet of Zittau, and the Amish operated Salemville Cheese Factory (Figure 4) in Green Lake County, which receives its milk supplies in ten gallon cans. However, many of the relatively small cheese factories, such as the Sartori Artisan Cheese in Linden, Iowa County (Figure 5), the Chalet Cheese Co-op’s factory north of Monroe in Green County, and the Nasonville Dairy cheese factory in Wood County produce over one million pounds a year.

Figure 5. Glacier Point Artisan Cheese Factory, operated by Sartori Artisan Cheese in the village of Linden, Iowa County. This relatively small factory processes over one million pounds of milk a year.

Other rural plants are far larger, including the Saputo Cheese factory in Fond du Lac County’s Town of Alto, the Lynn Dairy factory in Clark County, which serves a large population of both Amish and other dairy farmers, the Associated Milk Producers’ cheese factory in Jim Falls, Chippewa County, and the Land O Lakes factory in Kiel, Calumet County. While a few large cheese factories are located in metropolitan areas, the rural siting of Wisconsin’s cheese factories is clearly evident. Of the state’s ten largest cities, only two — Green Bay and Appleton — have commercial cheese factories, with the small Babcock Hall facility in Madison being located on the campus of the University of Wisconsin and operated by that institution’s College of Agriculture.

The remainder of this paper focuses upon describing the changing role of those former factories — almost all of which are located in rural areas — that once helped define Wisconsin’s dairy landscape. Many former cheese factories, including the state’s first, established in 1864 at Ladoga in Fond du Lac county (Ebling, et al. 1939), have simply been erased from the landscape. Indeed, no modern state historical marker commemorates the first cheese factory, although a small bronze plaque attached to a boulder was placed at its site in 1927 by the nearby Rosendale Men’s Club. It remains, now surrounded by flowers in a farmyard. The author has witnessed the loss of some former cheese factories, such as the one shown in Figure 6 that was falling into ruin when photographed a decade ago east of Bonduel in Shawano County. Now the adjacent field has been expanded to the intersection of the two rural roads. Others, such as the Brookside Creamery just west of Augusta in Eau Claire County produced cheese from the milk of nearby Amish farmers until 2009, but now some of the milk tanks have been ripped from the side of the building and the facility operates only as a milk receiving station, from where milk is shipped to another factory. Still other facilities, such as Laack’s Cheese factory in Brown County, remain in cheese related businesses, now producing cheese spreads and cutting and wrapping cheeses produced elsewhere, but not operating as a cheese factory. However, now it is far more common that surviving former cheese factories have uses unconnected with the dairy industry.

Figure 6. Ruins of a cheese factory in Town of Angelica, Shawano County, photographed in August, 1998.

Figure 7. Former cheese factory within Town of Burnett, Dodge County that is currently being used as a residence.

Of those former cheese factories still standing, the most common current usage is residential, such as a former cheese factory (Figure 7) north of Burnett in Dodge County. Among the 204 cheese factories listed on the Wisconsin Historical Society’s (2010) “Architecture and History Inventory,” over a third had undefined uses at the time of their listing, with the earliest listings dating to the 1970s. When listed, thirty-eight were then operating cheese factories, of which only fourteen now remain in business as cheese factories. When placed on the Historical Society’s inventory, fifty-eight former cheese factory buildings were clearly being used for housing. Undoubtedly many of the seventy-six structures whose contemporary use was undefined were also being used as residences.

Several structures were described in the historical society listing as having gone through a series of uses — such as first as a cheese factory, then as a tavern, before finally being adapted for residential use. Other inventoried usages for former cheese factories included retail stores, offices, farm buildings, storage facilities, as well as single examples serving as an apiary, an art gallery, a stable, a workshop, and a town hall. Inclusion in the inventory is highly influenced by the county of its location, with some counties, such as Dodge and Fond du Lac which at one time had large numbers of cheese factories, now having few, if any, included in the inventory. Although the listing is spatially biased and often outdated, it provides a hint of the changes that are sweeping Wisconsin’s rural dairyland. Furthermore, while the State Historical Society’s inventory noted that several former cheese factories were in ruins, the author’s attempt to locate just a small subsample of listed standing structures verified that several had disappeared, providing further evidence of the loss of the once common“ icon of Wisconsin’s dairy industry.

In several counties detailed inventories of cheese factories have been made. When the Lafayette County Historical Society attempted to inventory that county’s 171 current and former cheese factories (Ronnerud and Halfen 2004), they discovered that forty-three were either in ruins or were “gone.” In addition, thirty-eight were listed as having an “unknown” status, given that their exact locations were likewise unknown. As with the State Historical Society’s state-wide inventory, the most common usage of Lafayette County’s former cheese factories was residential, accounting for fifty-eight percent of those for which current usage information was available. The Iowa County Historical Society (2009) also undertook an inventory and detailed history of all 182 of the cheese factories that had operated in that county since the 1879. Only six cheese factories producing cheese from cow’s milk remained in operation plus one farm factory making Chevre from goats milk. Most (sixty-five percent) of the former cheese factories had disappeared from the landscape and an additional six percent of the structures were either abandoned or in ruins. Of Iowa County’s remaining former cheese factories, eighty-three percent of those still standing were being used as private residences. The Sheboygan County Historical Society published its history of that county’s 210 cheese factories nearly two decades ago, at which time fifty-three percent of the factories had already disappeared (Fisher 1992). At the time of the study forty-seven of the former cheese factories were used as residences, with three being listed as apartment buildings. While seven of the cheese factories were still making cheese, and another six were either processing cheese or other dairy products, currently only four Sheboygan County cheese factories remain open (WDATCP 2009). Thus, in all three counties where detailed inventories had been prepared, most of the former cheese factories that remain standing are now used for housing or storage.

Figure 8. Former cheese factory located in the Town of York in Green County, which is now being used as a residence. The lower part of this building near the large chimney is where cheese making occurred, while residential quarters were located in the upper floor. Cheese was often stored in the basement nestled in the slope of such buildings for aging.

Many of those former cheese factories that remain on the landscape display several architectural clues to their former usage. They are often conspicuous by the presence of the large chimney located in that portion of the structure where the boiler was once located. This is clearly seen in this example of a former cheese factory nestled in a valley southeast of Postville in Green County (Figure 8) and in another near Eldorado in Fond du Lac County (Figure 9). The cheese factory was often located at one end of a structure which often had a residential area at its opposite end, or manufacturing took place on the ground floor with a residential area above. Thus, within many former cheese factories the residential section continues in the same position as before, with the site of the factory being used for storage or as a garage. Some former cheese factories, such as this one (Figure 10) near Verona in Dane County, underwent considerable remodeling as they were converted into a residence, yet its large chimney remains to remind the viewer of its past history.

Figure 9. Former cheese factory in Town of Eldorado, Fond du Lac County, now being used as a residence. The large chimney and milk can loading dock are clues to this structures former use. Note the similarities with Figure 4, which displays the ramp that is currently used to load and unload milk cans at its loading dock.

Figure 10. Residence within a considerably remodeled cheese factory in the Town of Verona in Dane County. Note the large chimney that is partly hidden by the foliage to the left of the main part of the building.

The adoption of industrial cheese-making processes and faster transport have had a substantial impact on the viability of Wisconsin’s crossroads cheese factories. Although most of the over 2,800 cheese factories that once served the Wisconsin dairy industry have long ceased receiving milk, many remain a visible part of the landscape, although their uses have changed. The significant role that cheese factories played in their communities, such as that filled by the former Tonet Cheese Factory in the Belgian settlement area northeast of Green Bay, remains largely unheralded. However not all of the news is bad: within the small village of Hustler in Juneau County the former cheese factory, now sporting a fresh coat of paint, is being converted into an agricultural museum with financial support from the U.S.D.A.’s rural development agency. The small rural cheese factories that once operated throughout Wisconsin are now largely a part of the past, yet they played a key role in shaping the landscape of America’s dairyland and it is important to both recognize and preserve this vanishing landscape.

References

Cross, John A. 2001. “Change in America’s Dairyland,” The Geographical Review. Vol. 91, No. 4: 702-714.

Ebling, Walter H., Samuel J. Gilbert, and Gilbert T. Gustafson, Jr. 1931. Wisconsin Dairying (Bulletin No. 120: Wisconsin Dairy Statistics). Madison: Wisconsin Crop and Livestock Reporting Service.

Ebling, Walter H., W.D. Bormuth, and F. J. Graham. 1939. Wisconsin Dairying (Statistical Bulletin No. 200). Madison: Wisconsin Crop and Livestock Reporting Service.

Fisher, Edwin L. 1992. The Cheese Factories of Sheboygan County. Sheboygan: Sheboygan County Historical Society.

Iowa County Historical Society. 2009. Where have all the cheese factories gone?: the history of the cheese factories & creameries of Iowa County, Wisconsin. Dodgeville (WI) : Advantage Printing.

Lewthwaite, Gordon R. 1964. “Wisconsin Cheese and Farm Type: A Locational Hypothesis.” Economic Geography 40 (2): 95-112.

Ronnerud, James and Alan F. Halfen (eds.). 2004. Cheese Factories of Lafayette County, Wisconsin. Darlington: Lafayette County Historical Society.

Trewartha, Glenn T. 1926. “The Green County, Wisconsin, Foreign Cheese Industry.” Economic Geography 2: 292-308.

Wisconsin Agricultural Statistics Service. 2010. 2010 Wisconsin Agricultural Statistics. Madison: Wisconsin Department of Trade and Consumer Protection.

Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (WDATCP). 2009. 2009-2010 Wisconsin Dairy Plant Directory. Milwaukee: Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection

Wisconsin Historical Society. 2010. Wisconsin Architecture & History Inventory. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/ahi/advancedsearch.asp (last accessed February 9, 2011).