Worker Cottages: A Nineteenth-Century Great Lakes Urban House Type

Marshall McLennan

Eastern Michigan University

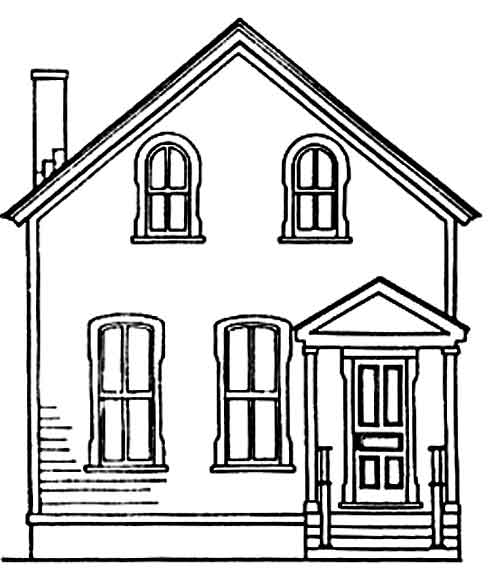

Fred Kniffen formulated the concept of “house type,” developed a methodology for field study, and legitimized dwellings as significant material culture artifacts worthy of scholarly attention.1 Cultural geographers and folk-life scholars who subsequently have followed Fed Kniffen’s lead in their study of American vernacular architecture have largely overlooked or ignored the Worker Cottage, a nineteenth-century house type most numerous in the industrial cities of the Great Lakes region (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prototype façade of a “working class” cottage, a dwelling promoted by pattern books in the 1840s and 1850s. These worker cottages were designed to accommodate to narrow urban lots. (McMillan 1987).

The methodology by which Kniffen identified house types was based on morphological analysis of dwelling features. He argued that colonial and many nineteenth-century vernacular buildings are artifacts associated with the traditional material cultures of various culture groups. His purpose was to identify regionally distinct American house forms, and explain these regionalisms in terms of the migrations of peoples bearing distinct sets of traditional cultural practices. According to Kniffen, traditional eighteenth- and nineteenth-century house types have best survived in rural areas and country towns not overwhelmed by the cosmopolitan ways of big cities. A rural bias, consequently, is built into Kniffen’s methodology, and his association of house types with material culture traditions explains why Kniffen and subsequent cultural geographers and folklife scholars interested in vernacular architecture, have largely ignored urban dwellings.

But there are reasons other than material culture associations to study dwellings as landscape objects. To paraphrase an observation by Pierce Lewis (1979) when we see changes taking place in the cultural landscape, it suggests to us that the culture is changing. For instance, when new house forms suddenly appear on the scene and old forms cease being built, something is going on in the cultural fabric.

Figure 2. A worker cottage with front-facing gable of the type built in Chicago from the great fire in 1871 until the advent of bungalows early in the twentieth century (Jennifer Roche April 27, 2007).

Figure 3. Worker class row houses, Beven Street, Baltimore (author).

The appearance of a new house type, the Worker Cottage, during the second half of the nineteenth century was emblematic of dramatic cultural and social changes taking place in America during that period (Figure 2). The nineteenth-century industrial revolution brought tremendous and ongoing changes to the cultural landscape of cities, one of which was construction of whole neighborhoods of inexpensive worker housing to provide shelter for factory laborers and their families. Early industrialization was centered in New England. Initially textile mill owners tried to provide housing for their workers, but this task soon devolved to speculative real estate developers. New housing forms like the Three-Decker tenement emerged to provide multiple-unit housing in many of the mill towns in New England. As industrialization spread to other parts of the country, the provision of urban worker housing yielded regionally distinct streetscapes. Row houses and half-a-double units (McLennan 2000) comprised other forms of worker housing, particularly in the Philadelphia – Baltimore – Pittsburgh triangle (Figure 3). Another house type, the Shotgun, was introduced into New Orleans at the beginning of the nineteenth century and diffused northward up the Mississippi into the Ohio River Valley (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Shotguns in a working-class neighborhood, Louisville, Kentucky (author).

A number of years ago one of my students claimed that she had stumbled across some Shotgun houses in Detroit. What she actually had seen was a similar-looking narrow single-family dwelling type locally called a “Corktown Cottage.” By the 1840s Detroit was easily accessible from the East by the Erie Canal and was undergoing rapid growth. Irish immigrants settled in what came to be called Corktown near the downtown riverfront. Initially they were accommodated in boarding houses and tenements. By the 1850s, the locally famous Corktown Cottages began to provide an alternative to the tenements (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Corktown Cottage, Abbot Street, Detroit (author).

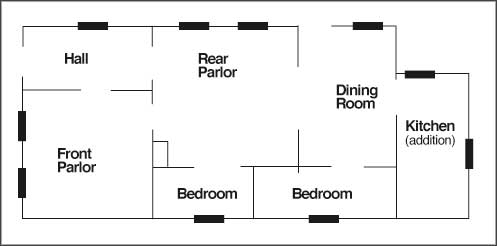

At first glance a Corktown Cottage does look like a Side-Hall Shotgun. A number of years ago, the Old House Journal published a small feature about these Detroit cottages and provided a representative floor plan (Palmer 1995). Although narrow, this cottage type accommodates two files of rooms (Fig 6). Their construction coincided with the publication in America of pattern books promoting cottage residences for “the working man.” Concurrently, traditional heavy brick or stone fireplaces were giving way to stoves, and post-and-beam framing was evolving into lighter braced-frame and then balloon-frame construction. All of these developments simplified labor requirements for building a house and met the needs of functionality and economy. In terms of morphology they represented a complete break with traditional cultural norms.

Figure 6. Floor plan of a Corktown Cottage. The width of the cottage accommodates one wide and one narrow room standing side by side. In other examples, the narrow bedrooms align directly behind the hall vestibule and the wide rooms are located one behind the other (Palmer 1995).

Prior to making an exploratory trip to Corktown, I initiated an internet-search for the “Corktown Cottage.” When I switched from a textural to an image search, I encountered morphologically identical dwellings called “worker cottages” ranging in location from Buffalo, New York, to Minneapolis, Minnesota. These images were particularly numerous for Chicago, where they are referred to as a specific house type called a “Worker Cottage” (Figure 7). The reality is that Detroit’s Corktown Cottage simply carries a local name for a widely distributed urban house type.

Figure 7. An 1890s Worker Cottage in the Lincoln Park neighborhood, Chicago (DePaul University Library Digital Collections, Wanda Harold, photographer 2000).

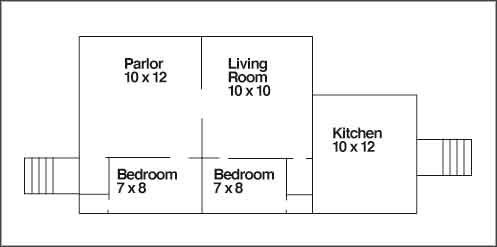

Turning to the literature for Worker Cottages, I found Joseph C. Bigott’s From Cottage to Bungalow; Houses and the Working Class in Metropolitan Chicago, 1869-1929 particularly enlightening. Using Kniffen’s morphological descriptors, we can define the Worker Cottage as a narrow rectangular-shaped dwelling, longitudinal in orientation with a two or three-bay gabled façade, two to three rooms in depth (a four to six room plan), and a height of one to one-and-a-half stories.2 Designed for a lot of 25-foot frontage, the cottage is two rooms in width, one narrow, the other more fully proportioned, with an average facade width of twenty feet (Figures 1 and 8). A raised basement is also common. Figure 9 depicts a representative Worker Cottage floor plan.

Figure 8. After the Great Chicago Fire, many Worker Cottages were constructed of brick. This example, located on North Hoyne Street, was built circa 1890 (Urban Real Estate n.d.).

Figure 9. Floor plan for a Worker Cottage from the 1870 “Illustrated Catalogue: Lyman Bridges Building Materials & Ready-Made Houses,’ reprinted in Bigott (44).

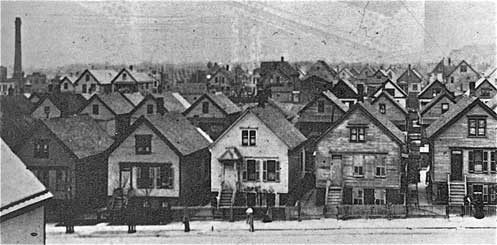

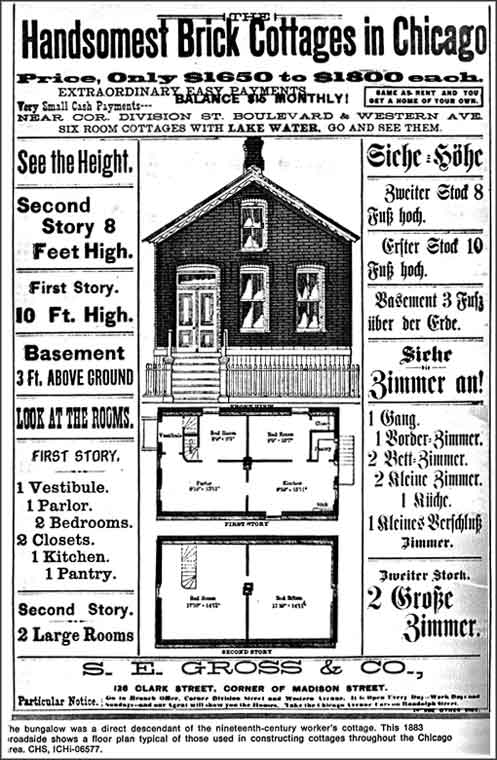

The rapid multiplication of Worker cottages in Chicago and its surrounding factory suburbs is associated with the city’s rise as a major focus of post-Civil War industrialization (Figure 10). Many industrial employers recruited laborers from abroad. This is illustrated by an 1883 broadside advertising the availability of “handsome brick cottages in Chicago,” which was printed with both English and German text (Figure 11, Chicago Historical Society 1883).

Figure 10. An unidentified Chicago neighborhood of wood-frame Worker Cottages, circa 1910 (Chicago Historical Society ICHi-00855, gift of United Charities, reprinted in Prosser 1981).

Figure 11. Printed in both English and German, this 1883 broadside advertised the availability of inexpensive brick cottages in Chicago for would-be factory workers. The broadsides were circulated in both the United States and Germany (Chicago Historical Society ICHi-06577, reprinted in Prosser 1981).

My Internet image search for “worker cottage” turned up dwellings of a variety of shapes and sizes. One has to make a case-by-case evaluation as to when the term is used as a simple descriptor (i.e., housing for blue-collar workers), and when it is intended as a more specific typological identifier. I found that when used as a typological designator, most of the examples were limited in geographic distribution to the Great Lakes portion of the old industrial belt, the region often referred to as “New England Extended.”

Figure 12. A Worker Cottage in Buffalo, New York, photographed first in 1885, then again in 2007. A porch has been added and the façade simplified.

Figure 13. The double-arch corner entry on this Worker Cottage in Toledo’s Birmingham neighborhood has Hungarian material culture precedents (Ligibel n.d.)

A Worker Cottage in Buffalo, New York, is depicted in 1887 and again in 2007 (Figure 12). Surviving Worker Cottages may be found in industrial cities and towns all across northern Ohio in such places as Cleveland, Akron, and Toledo. In the latter city, most of the Worker Cottages are the typical gable-front one-and-a-half cottages previously described, but five cottages in the Hungarian neighborhood of Birmingham have two oversized archways, serving as a corner entry (Figure 13). The same round arch entries are found in Hungary (Ligibel n.d.). In Detroit Worker Cottages are not limited to Corktown. In Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the “Old West Side” German ethnic neighborhood, Murray Court is lined with Worker Cottages (Figure 14). Despite the Irish-sounding street name, the Old West Side is the historic German quarter of town. Breweries, wagon manufactories, and foundries were once located nearby. Worker Cottages of similar morphology were also constructed in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Minneapolis, Minnesota (Figure 15).

Figure 14. A streetscape of Worker Cottages in Ann Arbor’s Old West Side (author).

Figure 15.Now a historic district, Milwaukee Avenue is a contiguous two-block development constructed in 1883, the first “planned workers’ community” in Minneapolis, Minnesota (Milwaukee Avenue Historic District, 1974).

By way of contrast, the southern portion of the old industrial belt, from Pittsburgh southward in the Ohio River Valley to Cincinnati and beyond, nineteenth-century industrial workers were housed primarily in row house tenements, reflecting Philadelphia - Baltimore Middle Atlantic influences (Figure 16). Although the housing built for factory workers throughout the industrial belt was mainly provided by real estate developers, and consequently not reflective of old housing traditions, it is remarkable that the worker cottage – row house distributional divide approximates the cultural boundary between New England Extended and what we might call “Middle Atlantic Extended.”

Figure 16. Industrial cities in the Ohio River Valley largely relied upon row houses like those seen above in Pittsburgh to provide shelter for factory workers. Final Pittsburgh Neighborhood Rowhouses, n.d.)

For the remainder of the nineteenth century, the Worker Cottage followed the “lumber-mill frontier” westward where it was sometimes utilized, especially in mining towns. In the Great Lakes region, the core area for the type, the Worker Cottage enjoyed a period of modernizing embellishment such as Queen Anne flourishes during the final years of the century. Then early in the twentieth century, the economic prosperity that followed in the aftermath of World War I brought with it a new house form, the Bungalow, for blue- and white-collar workers alike and quite suddenly the era of the Worker Cottage was over.3

In conclusion, because of its regionally significant distribution throughout the cities and towns of the Great Lakes region, the Worker Cottage needs to be added to the list of morphologically defined house types. It is a regionally manifested artifact of the industrial revolution, and is “important because it should be considered one of the first forms of fully industrialized housing for working-class Americans” (Kowsky n.d.)

Although seemingly well known to urban historians and geographers, amateur urban architectural enthusiasts and some informed realtors located in the Great Lakes region, we cultural geographers have largely overlooked the Worker Cottage in our typological overviews of vernacular house types. To a surprising extent, even urban historians from outside the Great Lakes region have ignored the Worker Cottage. For instance, Christine Hunter, in her otherwise very informative book length overview of American homes from colonial times to the present, in discussing new forms of single-family houses, jumps straight from Shotguns to Bungalows, making only a one paragraph reference to commercial developers erecting basic shelters for immigrants (142). These “basic shelters” are neither named nor described.

Finally, I believe that the cities and the industrial suburbs of the Great Lakes region comprise the innovative hearth for the development and utilization of the Worker Cottage and that it remains the core area where the bulk of such structures are to be found. My suggestion that the Worker Cottage is, to a large extent, a regional urban house type requires further verification through “eyes on the ground” fieldwork.

References

Bigott, Joseph C. 2001. From Cottage to Bungalow: Houses and the Working Class in Metropolitan Chicago, 1869-1929. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chicago Historical Society. ICHi-00855. n.d. Reprinted in Daniel J. Prosser. 1981. “Chicago and the Bungalow Boom of the 1920s.” Chicago History. 10.2:86–95.

Chicago Historical Society. ICHi-06577. 1883 Broadside reprinted in Daniel J. Prosser. 1981 “Chicago and the Bungalow Boom of the 1920s,” Chicago History 10.2:86–95.

“Final Pittsburgh Neighborhood Rowhouses” n.d. City-Data.com. http://www.city-data.com/forum/pittsburgh/608282-final-pittsburgh-neighborhood-rowhouses last accessed 30 March, 2011.

Hunter, Christine. 1999. Ranches, Rowhouses & Railroad Flats; American Homes: How They Shape our Landscapes and Neighborhoods. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Kniffen, Fred B. 1965. “Folk Housing: Key to Diffusion,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 55:549-577.

Kniffen, Fred B. 1936. “Louisiana House Types.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 26:179-193.

Kowsky, Francis. “Worker Cottages (1860-1920).” http://www.buffaloah.com/a/archsty/worl/work.html last accessed 30 March, 2011.

Lewis, Pierce F. 1979. “Axioms for Reading the Landscape: Some Guides to the American Scene.” In D.W. Meinig, ed., The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes. New York: Oxford University Press, 11-32.

Licata, Elizabeth. September 2008. “Inner City Farming, Buffalo Style.” Garden Rant. http://www.gardenrant.com/my_weblog/2008/09/ last accessed 30 March 2011).

Ligibel, Ted. “Birmingham Architecture.” n.d. http://www.sulinet.hu/oroksegtar/data/kulturalis_ertekek_a_vilagban/ Hungarian_american_toledo/pages/007_birmingham_architecture.htm last accessed 30 March 2011.

McLennan, Marshall S. “The ‘Half-A-Double House’: A Diagnostic Feature of the Delaware Valley Culture Region.” Paper presented to the Pioneer America Society, Richmond, Virginia, October 2000.

McMillan, Louise. 1987. A Field Guide to the Architecture and History of Allentown. Buffalo: Allentown Association.

“Milwaukee Avenue Historic District.” 1974. Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission. http://www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us/hpc/ landmarks/Milwaukee_Avenue_District.asp last accessed 30 March 2011.

Palmer, Steven. 1995. “Michigan’s Corktown Cottages.” Old-House Journal. 23.1: back cover.

Roche, Jennifer. April 27, 2007. http://theplacewherewelive.blogspot.com/2007/04/for-sale-last-little-cottage-in-lincoln.html last accessed 29 March 2011.

“1236 N. Hoyne, Chicago, IL 60622.” n.d. Urban Real Estate. http://www.urbanrealestate.com/property/1236-N-Hoyne-CHICAGO-IL-60622-L2F7B3GKL7XUK.html last accessed 29 March 2011.

“2679 N. Orchard St.; Workers Cottage.” 2000. DePaul University Library Digital Collections. Archives-LPNC1-1018 last accessed 29 March 2011.

Endnotes

1 Kniffen’s methodology is explained in “Louisiana House Types.” His presidential address to the Association of American Geographers “Folk Housing: Key to Diffusion,” comprises the groundbreaking call to arms for geographers to involve themselves in regional house-type studies. [Return to text]

2 Bigott and other Chicago-based scholars group two and two-and-a-half story upright houses in the Worker Cottage category. Although these houses have traditionally housed a working population, because of their greater scale and the ease with which they can be confused with two-family flats, I prefer to categorize the two-story houses as the “Upright” house type. This is analogous to the distinction commonly made between the I-House and the I-Cottage. The term “Upright” is derived from the “Upright-and-Wing House.” [Return to text]

3 In my presentation of this paper in Castleton, Vermont, I compared the respective morphologies of the Shotgun, Worker Cottage and the Chicago Bungalow. In this paper I have narrowed the focus to the Worker Cottage. [Return to text]