Curt Teich Card 6A-H959: A Fact Broadcast in a Sea of Imagination

Keith A. Sculle

Popular histories customarily abound with postcard images. They bear proof that certain places — often individual buildings — existed and had certain architectural features. They help viewers pause in the written text of abstractions to live vicariously in the very time and at the site of the building shown.

Postcards can sometimes also serve as the most accessible fact of a particular building’s very existence in scholarly history’s effort, less to entertain, than to build an enduring record. Postcards’ relative advantages to popular and scholarly audiences came home again in my on-going interest about Vincennes, Indiana.

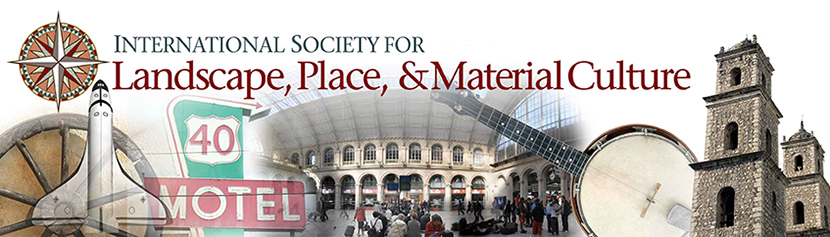

Figure 1.

Maurice Thompson (1844-1901), an Indiana writer had his most popular work, Alice of Old Vincennes (1900), published a few months before he died. He wrote in the tradition of local color, a genre in the late-nineteenth century that brought regions to life in print by utilizing local figures and local speech, customs, and physical geography. He understood small town Vincennes’ earlier importance, in the eighteenth century, to the competition for European colonial empire in North America and America’s own expanding empire when George Rogers Clark wrested control of it from the British in 1779. Alice Roussillon was the novel’s heroine. Born of an old and distinguished English colonial family and raised among Native Americans, French trader Gaspard Roussillon adopted her at age twelve. She became instrumental in Clark’s conquest and fell in love with one of his officers. A heroine, the West, and the American Revolutionary War era — many ingredients were blended for a winsome and heroic tale. Or, as the publisher explained to readers, “the history and romance will, it is hoped, make a vivid and authentic impression . . . which must forever be kept sacred . . . .” Which was it? Fact or fiction?

Alice of Old Vincennes emerged from Thompson’s literary talents turned on a dreamy-eyed cast of mind. M. Placide Valcour, a descendant of an early French family in America, introduced Thompson to a genuine colonial document that engaged him. Thompson made more of it than there was. At the time of the introduction, Thompson was at Valcour’s house on the Louisiana Gulf Coast and mining his host’s knowledge of the French in early America when his host showed him a letter by Gaspard Rouissillon. It catalyzed the factual researcher turned novelist. In Thompson’s dedication of Alice of Old Vincennes, “a mildewed relic of the year 1788, which you so kindly permitted me to copy, as far as it remained legible, was the point from which my imagination, accompanied by my curiosity, set out upon a long and delightful quest.” Valcour’s own considerable talents (he held an M. D., Ph. D., and LL. D) turned to both literature and science. But, as Thompson recalled, “You laughed at me when I became enthusiastic regarding the possible historic importance of that ancient and, alas! fragmentary epistle . . . .” While Valcour’s scientific sense saw limitations in the document, Thompson’s literary preference thrust him toward its possibilities.

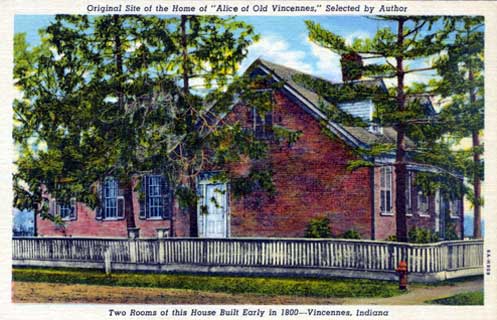

Figure 2.

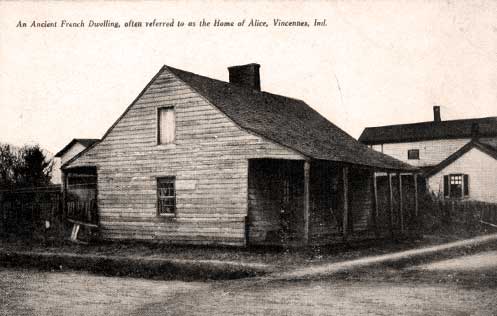

Figure 3.

Firm fact or misty fantasy — which would prevail? After finishing his writing, the novelist dwelled on the two opposing viewpoints. The last paragraph of Thompson’s introduction to Valcour: “Accept, then, this book, which to those who came only for history will seem but an idle romance, while to the lovers of romance it may look strangely like the mustiest history.”

French architecture survived in Vincennes long after the American majority prevailed. These buildings were enduring facts. Whereas, the novel’s publisher wanted the history remembered, Vincennes cared less at the time if historical buildings served that mission. At the turn of the twentieth century, Vincennes was no longer a center in the fur trade but a center in an industrializing nation’s agricultural heartland. On the second page of his book, Thompson grounded his introduction on known landmarks. These were a cherry tree that once was a reference point for locating Roussillon’s house, and, at the novel’s writing, the Catholic church. Thompson conjured Vincennes’ visage at the time of his writing. “The new town flourishes notably and its appearance marks the latest limits of progress. Electric cars in its streets, electric lights in its beautiful houses, the roar of railway trains coming and going in all directions, bicycles whirling hither and thither, from brougham to pony-phaeton . . . .” By current standards, early architectural survivals would be cherished landmarks, ballast amidst swirling modernity. A few towns in Thompson’s time realized the potential of adding historical landmarks gilded by regional novels to their burgeoning economy. Ramonawas an asset which San Diego’s boosters allied to their cause. Shepherd of the Hillslikewise benefitted those re-inventing southwest Missouri as an Ozarks paradise with Branson at its center. In 1907, however, Vincennes witnessed, in the Vincennes Commercial’s words, “Two more Old French Houses Torn Down to Make Room for Modern Dwellings.” Gain, not loss characterized these events: “Thus, the old landmarks of the old town are giving way to the more modern needs of our progressive city,” the newspaper boasted. One of these houses local tradition attributed to be “The Home of Alice of Old Vincennes.”

Fact and fiction had gone separate ways in Vincennes. Perhaps the people of the town reasoned that, since Alice never existed except in print, why grieve the loss of a house said to have been hers? Progress-oriented people celebrated economic growth and, if no significant outpouring of lament about the building could be sensed, Vincennes still enjoyed the novel. Former President Grover Cleveland asked about the novel when, shortly after its publication, he visited Vincennes. This likely flattered the citizenry. Historian Brian Spangle has noted that, in 1902, the town enjoyed a play based on the novel.

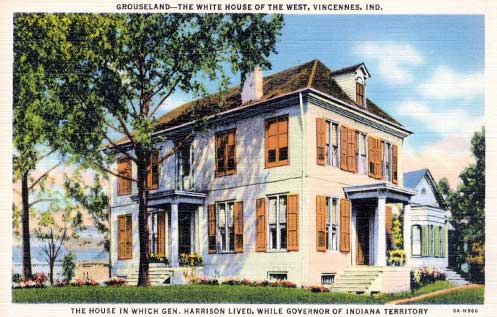

Figure 4.

However, what we are most aware of now is Curt Teich postcard 6A-H959 (figure 1) of the building alleged to have been “The Original Site of the Home of ‘Alice of Old Vincennes’.” (Curt Teich was one of the largest postcard producers.) At least three other postcards showing a different building (wooden, not brick) are known (figure 2) and, two recent pictorial histories hold that it was the “supposed” home of the “fictitious” heroine of the novel. Alternatively, the Curt Teich version asserts that the brick house shown on their card was the site of the original home. The edge of this card carried the note, “Selected by Author;” this likely implied primacy among rival postcard claims. Curt Teich archival records include the name “A. A. Arnold, Vincennes” on the back of the image. It and several other Curt Teich postcards (figure 3 and 4) are likely the work of Allie A. Arnold (1889-1971). He was not only active in local politics, holding the office of City Clerk, County Clerk, and County Assessor. His enthusiasm for things local also inspired him to write newspaper columns and host a radio show, the latter of a retrospective or historical nature. Curt Teich published the card at the height of historical appreciation surrounding dedication in 1936 of the George Rogers Clark Memorial on the banks of the Wabash River at Vincennes’s western edge. F. W. Woolworth probably ordered the postcard as one of a series, offers Debra Gust of the Curt Teich Archives. More people probably still know of the Curt Teich version than the wooden building depicted on the other postcards because of Curt Teich’s mass printing and Woolworth’s voluminous sales. Thus, was broadcast a bit of fact underlying a nearly forgotten fiction about the Alice of Old Vincennes.

Acknowledgements

Brian Spangle of the Historical Collection, Knox County Public Library, and Debra Gust of the Curt Teich Archives.

All postcards are from the author’s personal collection.

Sources

“Allie A. Arnold ‘The Oldtimer,’ Dies.” 1971. Vincennes Sun-Commercial. Mar. 5.

Day, Richard. 1994. Vincennes: A Pictorial History. St. Louis, MO: G. Bradley Publishing, Inc.

Gust, Debra. 2010. Email to the author. Sept. 20.

Spangle, Brian. 2010. Email to author. Sept. 18.

Thompson, Maurice. 1900. Alice of Old Vincennes. Indianapolis, IN: Bowen-Merrill Co.

About the author

Retired Head of Research and Education, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, Keith A. Sculle, Ph. D., has written numerous articles about aspects of the imagined and real landscape in America.